Museum of Arts and Crafts (Kunstnijverheid)

The first museum in the Netherlands, entirely dedicated to applied art, was the Museum of

Arts and Crafts (Museum van Kunstnijverheid) in Haarlem. (1877-1927). This museum was located in Paviljoen Welgelegen, the current provincial government building.

The founder of this museum was Frits van Eeden (1829-1901), father of the well-known writer Frederik van Eeden. He was destined to take over his father’s flower nursery in 1858. In 1859, he succeeded his father as general secretary of the Netherlands Association for the Promotion of Industry (NVN), after which his career within the NVN board began. Frits van Eeden disliked the business world and therefore sold the nursery in 1866.

The world exhibitions held in Europe from 1851 onwards were the cause of the emergence of arts and crafts museums. At these exhibitions, various countries presented their raw materials, products, inventions, and art and culture. World exhibitions served as manifestations of civilisation and progress and for the promotion of trade. The World Exhibition of 1851 in London prompted many European countries to compete against France, a country that had played a prominent role in Western European art and culture for centuries.

The result was that arts and crafts became important in Europe. Many countries founded arts and crafts museums and institutes. The NVN’s plan to set up an arts and crafts museum in the Netherlands arose in 1872. The NVN felt the need for such a museum and wanted to follow the example of the Victoria and Albert Museum founded in London. Moreover, a museum would be a nice project to celebrate the NVN’s 100th anniversary in 1877. In 1877, the new Museum of Arts and Crafts opened its doors. Frits van Eeden became director of this new museum. He would continue to hold this position until 1899.

The NVN reports showed that the Netherlands lagged far behind other European countries in terms of arts and crafts. The poorer artistic quality and lack of craftsmanship were notable. According to the NVN, a lack of knowledge was due to the disappearance of the guilds and the rise of mechanical production. Moreover, the middle class at the time preferred foreign products that were reasonably affordable because no import duties were levied on them. And furthermore, according to the NVN, it was uncertain whether the Dutch citizen had a sense of beauty and quality. The conclusion was reached that both producers and consumers needed to be educated. This could be done through museums, training programs, and publications. The NVN advocated for the establishment of craft schools and the introduction of drawing education. In 1879, the ‘Teekenschool’ (Drawing School) for Arts and Crafts was founded in Haarlem. This is seen as the first educational institution for designers in the Netherlands.

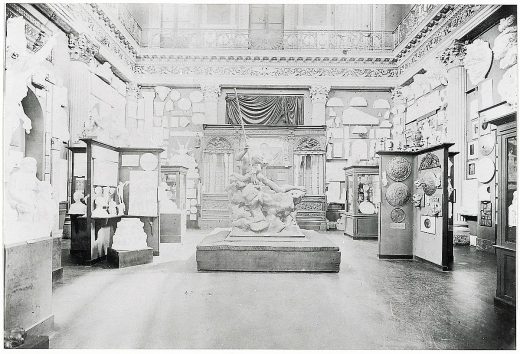

The collection of the Museum of Arts and Crafts was arranged chronologically. It began

with the architectural orders and the art of the ancient Greeks and Romans, followed by the Byzantine Empire, then the art of the Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, and Rococo periods. Smaller objects were sorted by material type. A striking aspect of the collection was that it largely consisted of copies. Stylistic purity was the most important starting point for Van Eeden, whereby a good copy was preferable to a bad original. According to him, arts and crafts museums had to give a pure representation of certain styles, antique or modern.

Van Eeden believed that one should look beyond the Dutch borders. This was the reason that many objects from Asia were also included in the collection. Therefore, a separate room in the museum was dedicated to Moorish (Arabian) objects from the seventh to the fourteenth century. He was also interested in the history of other countries, which he compared with Western civilisation. He found that Eastern cultures, such as the Indonesian one, were much closer to nature than Western European cultures.

In his eyes, arts and crafts in the East were on a higher level than those in the West. According to him, Western Europeans were less independent in their sense of art due to a multitude of styles than the population of Borneo. Van Eeden admired Indonesian arts and crafts and saw industrialisation as a threat to all art. His views were very innovative at the time.

In the mid-1880s, Van Eeden devoted himself to folk art, particularly wood carving for foot warmers, clogs, butter molds, and related objects. The aim was to save the dwindling craft of wood carving from decline, due to industrialisation, and to breathe new life into it. This revaluation of folk art closely aligned with the historicizing design of late nineteenth-century culture. This revaluation was clearly visible at the world exhibitions of 1895 and 1900, where a lot of Dutch folklore was shown. In 1891, a period room in old-Dutch style was even set up in the Museum of Arts and Crafts. A few years later, in 1902, an old-Dutch kitchen was added, and in 1907 a Hindelopen period room was included.

After Frits van Eeden stepped down in 1899, Eduart van Saher took over his position. He had plans for expansion. The Colonial Museum, which was also housed in Paviljoen Welgelegen, was going to move. The Museum of Arts and Crafts was granted permission to add the rooms of the former Colonial Museum to the museum. Unfortunately, the expansion was delayed due to the First World War. Eduart van Saher did not live to see the expansion, as he died in 1918. A new building was being worked on in Amsterdam where the Colonial Museum would merge with the Colonial Institute. Now known as the Wereldmuseum (formerly Tropenmuseum).

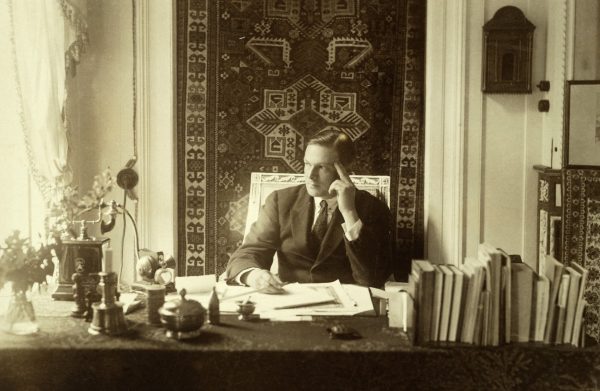

In 1918, a new era began after the appointment of Otto van Tussenbroek (1882-1957) as the new director. Van Tussenbroek came from a notary family. In his youth, he was friends with Dirk Nijland, son of Art and Antique collector Hidde Nijland. He regularly visited the Nijland family where he met artist Jan Toorop, who was a close friend of the family. This brought Van Tussenbroek into contact with art. He reluctantly studied notarial law, after which he briefly worked at the trading company Muller, owned by Anton Kröller. After this, Van Tussenbroek chose a life as a painter. He exhibited caricatures and Parisian cityscapes. He also worked as a publicist, including for Elsevier.

He was convinced of the effect of temporary exhibitions, and attached great importance to providing information and enthusiastically engaging people in art. He started art courses through guided tours, a new phenomenon at the time. The tours he gave were very successful.

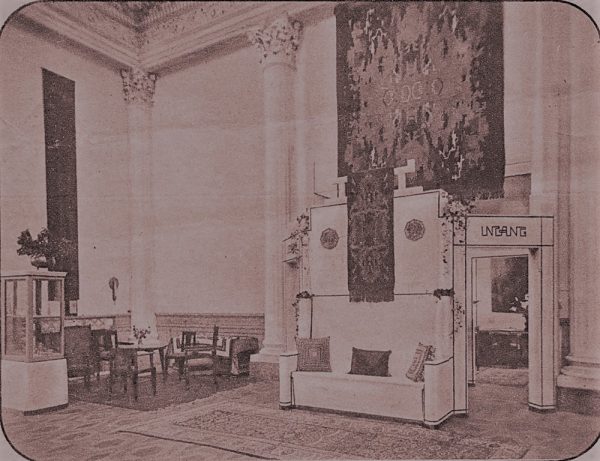

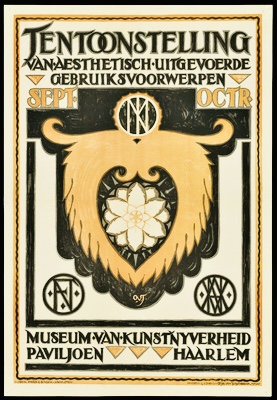

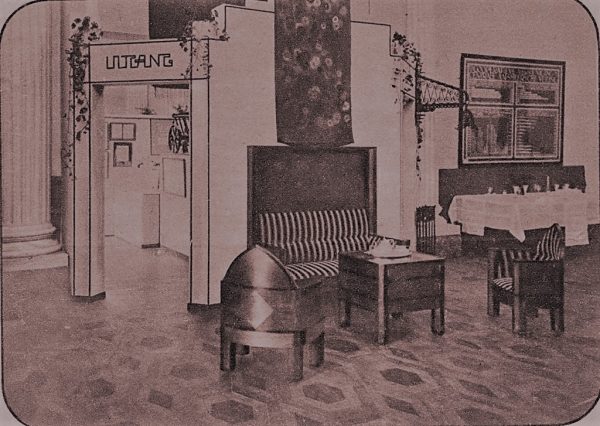

In 1919, Van Tussenbroek held his first temporary exhibition, called Exhibition of aesthetically executed utility objects.

The goal of this exhibition was to promote cooperation between the manufacturer and the

artist. He made a strong impression with this temporary exhibition. The building had been refreshed and the vacated spaces of the former Colonial Museum were added. This temporary exhibition provided a broad overview of contemporary arts and crafts. Work was shown

by Sjoerd de Roos, Jaap Gidding, Piet Zwart, and Jaap Jongert. According to critics, work by

Amsterdam School architects such as Michel de Klerk and Joan van der Meij was missing.

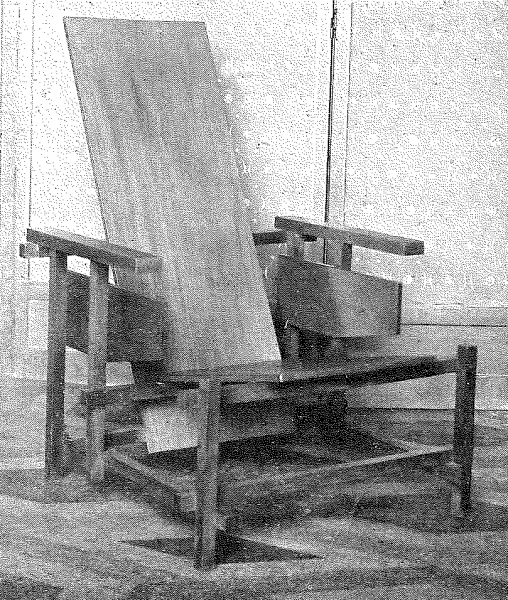

Work by artists working in the vein of the De Stijl art movement was exhibited for the first time at this exhibition. Work by Theo van Doesburg and Piet Zwart was shown. Piet Zwart had converted to modernism, as evidenced by a chair he submitted for this exhibition. Gerrit Rietveld showed his slatted chair here, which would later become his most famous design. At that time, this chair did not yet have its iconic colours (red, blue, black, and yellow) but was only stained. Designer and critic Cornelis van der Sluys described the members of De Stijl as a bunch of rebels, “Bolsheviki”, following this exhibition.

In the summer of 1920, Van Tussenbroek held a temporary exhibition called Weaving Art and Ceramics. This exhibition was highly appreciated for its harmonious arrangement. He said about arranging: `To place things in such a way that they never hinder, never disturb each other, always complement, always support; bringing unity in such a way that the objects stand free from each other, but still strongly retain the binding element’

The submissions for this exhibition came from all over Europe and were supplemented with modern Dutch work. For example, there was a large submission from the Wiener Werkstätte with work by Josef Hoffmann, Joseph Olbrich, and Rudolf Bayr. There was also a large French submission with work by ceramists Lachelnal, Emile Decoeur, and Alexandre Bigot. This was supplemented with work by Dutch ceramists Willen Brouwer, Jaap Gidding, Chris van der Hoef, Chris Lanooy, Bert Nienhuis, Theodoor Colenbrander, Vilmos Huszar, and Lion Cachet. It was special that demonstrations of Egyptian basketry were given during this exhibition.

After this, Van Tussenbroek organised an exhibition on African art. He saw African art as art with a wondrous power that testified to the ‘childlike uncorrupted’ and ‘the unstained soul-purity’ of the ‘savages’. African art was very popular in the early 1920s. Artists such as Picasso were inspired by this art. This also applied to Dutch artists Theo van Reijn and Van den Eijnde. This non-Western art had also entered the Amsterdam School. All of this was thanks to exhibitions at the Museum of Arts and Crafts. By holding exhibitions about Jan Toorop and Johan Thorn Prikker, Van Tussenbroek brought up a religious aspect. The artist Jan Toorop, born in the Dutch East Indies, later converted to the Roman Catholic faith, thereby connecting East and West. Van Tussenbroek was the first to draw attention to Jan Toorop’s Indonesian background. About Jan Toorop, he said: ‘He is the man who, as an artist, gives us something holy from God’s grace’. The religious influence was also visible in the work of Johan Thorn Prikker, who designed stained glass windows and frescoes for various churches, among other things.

Despite all the successes Van Tussenbroek achieved with the museum, the adjacent Haarlem School for Architecture, Decorative Arts and Crafts was in severe financial trouble and the museum’s financial deficit also began to increase. Although the school and the Museum of Arts and Crafts had their own budgets, they had the same overarching board. In the autumn of 1921, the municipality of Haarlem questioned what benefit the city had from the museum. The municipality considered significantly reducing the subsidy. Pending this decision, Otto van Tussenbroek decided to resign honourably, citing that the possibilities for the museum to function were so compromised that he considered the situation untenable.

In 1923, Van Tussenbroek was succeeded by Willem Penaat (1875-1957), a renowned architect and furniture designer. He was one of the driving forces behind the New Art movement in the early 1900s. Penaat was also one of the initiators of De Woning (The Home) in 1904, one of the first design shops in the Netherlands. As chairman (1913-1922) of the VANK (Association for Arts and Crafts Industry), he championed the interests of designers wherever he could. Partly thanks to him, the Institute for Decorative and Industrial Art was established, which mediated in commissions from the industry. Penaat was a man of authority and had many connections.

He realised the situation the museum was in and urged the overarching board that it was necessary to obtain support from the State and the municipality. His main intention was to give the museum a grander appearance. To achieve this, he proposed a merger with the Institute for Decorative and Industrial Art. Unfortunately, the finances were insufficient for this, making it difficult to develop plans for the future.

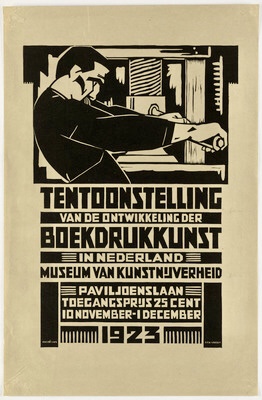

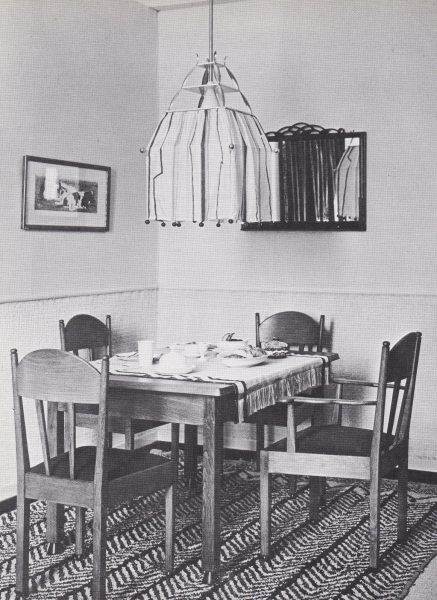

Due to the limited budget, only a few temporary exhibitions took place. Artists who made quality work could rent spaces in the museum. In 1925, a temporary exhibition was held, this time organised by the League for Art and Industry (Bond voor Kunst en Industrie), which attracted many visitors.

For this exhibition, architect and designer Hendrik Wouda designed several period rooms in which recent work was shown. Participating companies included: Leerdam Glass Factory, Pander and Zonen, linen factory E.J. van Dissel, and Metz & co. The exhibition was opened by Marijn Cochius, director of the Leerdam Glass Factory. In the early 1920s, there was a discussion about the right to exist of various museums in the country. The result was that the government established a museum committee to end this discussion.

This commission made an inventory of all museums in the Netherlands and had a great influence on the decision-making regarding the Museum of Arts and Crafts. Their report distinguished between state-owned museums and non-state-owned museums, which meant that the latter could only receive state subsidies if the municipality and the province also contributed. In this way, a distinction was made between first and second-class museums. The Museum of Arts and Crafts saw itself as a museum of national importance but did not belong to the state-owned museums.

However, for the municipality of Haarlem, this national importance was precisely the reason for reducing the subsidy. The municipality’s decision to cut subsidies also endangered the State’s contribution. The State had set its sights on Paviljoen Welgelegen, where the Museum of Arts and Crafts was located, for a new seat for the province of North Holland. The municipality of Haarlem had previously designated a construction site for the building of a completely new Provincial House, but the State rejected these plans due to excessive costs. The adjacent School for Architecture, Decorative Arts and Crafts was also performing poorly, making its continued existence uncertain. The school definitively closed down in April 1926. There were too few students, causing the government to withdraw the subsidy. Both the school building and Paviljoen Welgelegen were claimed by the State for the province. As a result, the Museum of Arts and Crafts could not continue to exist. Since then, there has been no museum in the Netherlands entirely dedicated to applied art and design.